As Covid restrictions wane, restaurants and bars are facing yet another difficult challenge: finding employees. In fact, our clients tell us that the labor shortage has become such a crisis that they cannot operate 7 days a week, or are unable to open for lunch; and that they fear they may not be able to staff for the anticipated summer demand. Some operators are so desperate to find employees that they are offering large cash bonuses, trying to poach employees from other restaurants or thinking of eliminating servers altogether. McDonalds just announced a 10% pay raise for every one of its employees. Amazon, Walmart, Costco, Chipotle, Darden, and many others have announced wage increases to combat what Domino’s Pizza called “one of the most difficult staffing environments that we’ve seen in a long time.”

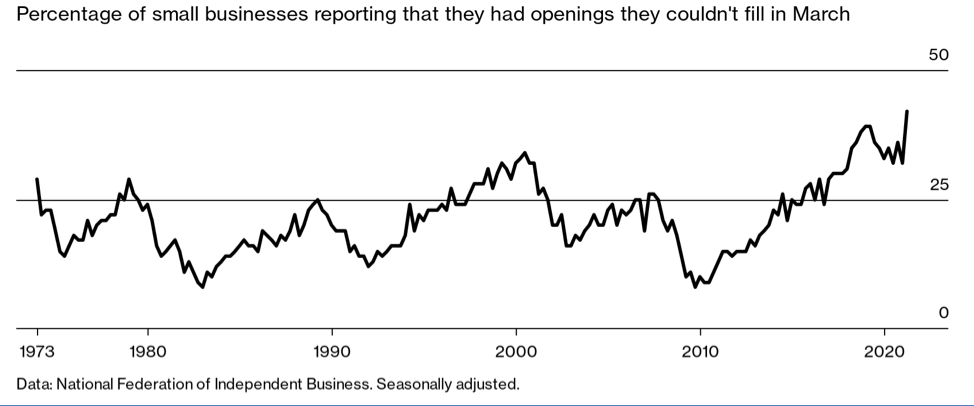

A record share of small businesses have unfilled jobs

There are a variety of reasons for the labor crunch but there is no doubt that it is a serious threat to the hospitality industry’s recovery. Last month the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) reported that 42% of business owners have job openings they cannot fill. That’s the highest reading in the NFIB’s, 48 year history.

The NFIB’s report confirms what our clients have been telling us: “owners continue to have difficulty finding qualified workers to fill jobs as they compete with increased unemployment benefits and the pandemic keeping some workers out of the labor force”. Bloomberg News reports that “the number of vacancies exceeded hires by more than 2 million, the largest gap on record.”

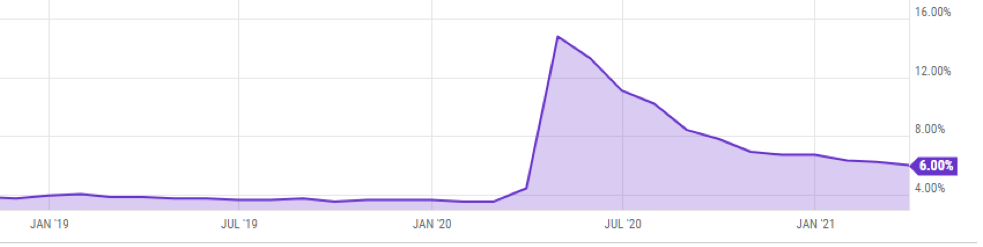

Unemployment rates have improved quickly since the spring, yet, at 6%, unemployment is still 60% higher than the pre-Covid average (see chart).

Which is puzzling: if there are still lots of people out of work, why is it so difficult to find employees?

Competing with the government for employees

There are multiple factors involved, some of which are inevitable coming out of Covid, although the biggest factor appears to be caused by overly generous government policies: when you pay people not to work, it shouldn’t be any surprise when they choose not to work.

Many people are still unvaccinated and, understandably, fearful of returning to a workplace because of the risks of getting Covid. Others would like to work but can’t because schools are operating at half-capacity and they cannot afford childcare. We also see evidence that some workers are just taking their time choosing a job out of the hundreds available; they’re able to be picky because everyone is hiring. These factors should all improve over the next couple of months.

Unfortunately, many former restaurant workers have permanently left the industry – and that won’t improve quickly. That really isn’t shocking given the fact that our industry has not been able to offer consistent employment over the past 14 months. In some areas, we’ve been entirely shut down, then allowed to re-open with limited capacity, then shut down again a second time.

But the biggest obstacle in the labor market is that, in effect, employers are competing with the government for employees. With the “Pandemic Additional Compensation” program adding an additional $300/week to unemployment benefits in the U.S., there is little incentive for anyone to take a low-wage job. In California, for example, unemployment payments top out at over $700/week now – which is the equivalent of $20 per hour over a 35-hour/week!

In early May President Biden said that he does not “see much evidence” that the generous unemployment benefits have deterred people from taking jobs, adding that “Americans want to work.” That defies logic. If a worker will make more on unemployment than they would working full-time for $10 or even $15 an hour, many will choose not to work. In fact, it’s easy to imagine that many won’t be interested even in a job paying $25/hour because, in many states, that would only amount to a couple of hundred extra dollars working full-time compared to what they can make for not working at all.

Attracting workers this summer

In the U.S., the federal government’s extra unemployment payments won’t end until early September 2021. So what can a restaurateur or bar owner do this summer to attract employees?

Raising wages is one obvious option. The reality is that you are competing with other businesses for the employees who actually do want to work. So if you are paying a couple of dollars an hour more than the other job postings, you’re going to get more applicants. The problem, of course, is that our industry already operates on very low margins. Paying an extra 20% in wages would push many restaurants into the red.

In order to avoid getting locked into permanently higher wages, paying a one-time bonus for new employees (and/or when your current staff recruits a new employee) is becoming increasingly common. Most operators are structuring the bonus so that it is not paid out until the employee has stuck with the job for at least two or three months (it would be a disaster if the employee pocketed the bonus and promptly quit). Many job boards in my area list bonuses of $300, $500, or, in the case of this ad I saw today, even $1,000 for new employees.

Higher wages are only sustainable, however, if restaurants also raise prices. Historically, it’s been difficult to raise menu prices in an industry with so many competitors. But because so many restaurants have not survived the Covid lockdowns, the survivors now have fewer competitors and, hence, some room to adjust pricing.

Way back in an April 2020 white paper, I argued that, post-Covid, “the ‘new-normal’ needs to result in more rational restaurant economics, starting with restaurateurs refusing to set prices that are simply too low”. And I forecast that there would be fewer competitors now, which would allow restaurants to “raise prices to a level that might finally result in a reasonable profit and return-on-investment.” According to the NFIB, this is actually happening: 36% of small business owners report that they intend to raise selling prices.

We’re also seeing many restaurateurs restrict their operating hours so that they don’t need quite as many employees. Depending on your business, it might make sense to close for lunch, or perhaps to close entirely on your slowest day.

I think we are all going to have to change our expectations, starting with dropping the idea of hiring only experienced restaurant workers. If we are going to have enough employees this summer, most of us will have to hire inexperienced people and then spend more time training them.

We might also have to consider hiring younger employees. My 15-year old daughter wants to work but has found that most help-wanted ads only accept applications from older kids. A smart operator might be wise to lower their age requirements for certain jobs. We might also consider eliminating the job screens that eliminate ex-felons from consideration.

Finally, some full-service restaurants have changed their business model to eliminate servers. Guests order at a counter, or through an app, and the order is delivered to the table by an expediter. This will work for some concepts but requires careful thought. The risk is that if you do not meet your guest’s service expectations, you could permanently alienate loyal customers.

I saw this first-hand when a group of six of us had dinner at a famous San Diego craft brewery in April. We had always enjoyed our previous visits. We were a little taken aback when our hostess showed us a QR code and told us to order on their app. After the predictable struggle to get the app downloaded and working on everyone’s phone, some of us had questions about the menu or wanted a recommendation – but there was nobody to ask. When one of the dishes was delivered cold, it took us way too long to find someone to replace it. The overall experience definitely did not live up to our prior positive experiences. The whole night seemed sterile; cold; fundamentally, it felt like nobody cared about us and we felt no connection at all to the restaurant or their staff. If we’d been prepared for the change I don’t think we would have been quite as disappointed. I think the restaurant made a mistake in neglecting to explain their new service model when we made the reservation; expectations are crucial.

In contrast, I often think about my elderly parent’s loyalty to their favorite restaurant, which they visited every Saturday night for 15 years. They liked one server in particular and always asked to sit in her section. A few years ago I noticed that they had stopped going to that restaurant and I asked them if they had had a bad meal. No, they told me, it was simply that their favorite server had left. Their strong connection to one great employee had kept them coming back every week, despite having hundreds of restaurant to choose from. I hope we never lose that kind of hospitality that has always been at the heart of our industry.

--------------------------------------------------------

About the Author:

Ian is Sculpture’s Regional Director for the west coast. For three decades, Ian has helped operators improve their profit margins and pour costs, primarily through inventory control. With the looming labor shortage, he is on a quest to uncover the best ideas for finding and retaining employees.

.jpg?width=520&height=294&name=Copy%20of%20Sculpture%20Hospitality_Owners_March%20(9).jpg)